Best practice: optimizing fonts

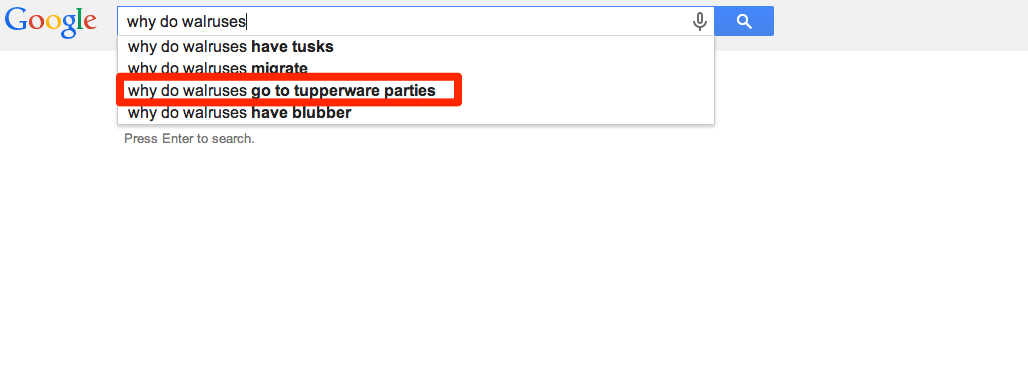

In recent years, the use of fonts on the web has exploded (both in terms of the number of existing fonts and the number of sites using them).

As usual, the Web Almanac is a mine of information, especially via the chapter dedicated to fonts. We learn that the two main suppliers of web fonts are Google and Font Awesome, the latter consisting in the provision of icons. Beyond the potential cost on performance and environmental impacts, some countries have already established that this could contravene the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation).

Let’s see what good practices can reduce the impact of fonts on the web.

Existing reference systems

The fonts are mentioned in the UX/UI family of the RGESN (Référentiel Général d’écoconception de services numériques) :

- 4.10 – Does the digital service use mostly operating system fonts?

They are also found in GR491 (Responsible Digital Service Design Reference Guide):

- Do you limit the number of fonts loaded?

- Do you give preference to system fonts?

- Are the number of fonts and font variants called (fat, characters used in the project) limited?

Finally, the 115 web ecodesign best practices also mention them:

Good practices

Objectives

In order to reduce the impacts of fonts, several best practices are applicable:

- Give preference to standard/ system fonts : This avoids additional requests

- Use an optimal compression format (today, it is the WOFF2 format). Online tools as Everything Fonts can provide this conversion.

- Limit the number of variants used or use a variable font

- Load only the characters that are really used (for example via a subset)

When ?

These good practices must be implemented as soon as the visual design of the service is done in order to favor standard fonts as much as possible. If this is not possible, then limit the number of variants to be loaded. Finally, when fonts are integrated, use the woff2 format, variable fonts and make sure to load only the characters or languages actually used.

Ease of implementation

If the site is already online, it can be complicated to change the font used. On the other hand, technical optimizations are easy to implement (format, variable font, Subset).

Estimated gains

These best practices reduce the number of HTTP requests and the volume of data transferred.

Specific cases

Google Fonts

To avoid problems with the RGPD, it is recommended to host Google Fonts yourself.

If variable versions are not available for all, some creators offer these versions for free. In addition, the Google API allows you to directly create a Subset with a request of this type: https://fonts.googleapis.com/css?family=Montserrat&subset=latin

Icons

Icon fonts are quite common. Using them directly may imply loading many icons that will not necessarily be used. The best way to use icons is to use each of them directly in SVG format. In this form they can be embedded directly in the HTML (without any additional HTTP request). If an icon font must be kept for practical reasons, limit the file to the icons actually used.

Case study

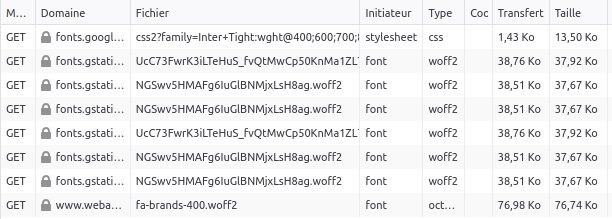

As part of the support Docaposte teams receive for their corporate site, fonts are often a separate project.

The fonts used here are two Google Fonts: Montserrat and Barlow. The site being already online, it is complicated to impose the use of standard fonts.

To avoid violating the GDPR and to improve site performance, fonts are hosted directly on Docaposte’s servers. In a second phase, a dedicated subdomain could be set up to eliminate the need for cookies.

The integration in the form of a variable font requires some additional adjustments, especially in the style sheets. In the meantime, it was decided to apply two best practices:

- Propose the files in woff2 format rather than woff

- The site being proposed only in French and English, a Subset was created keeping only the Latin alphabet.

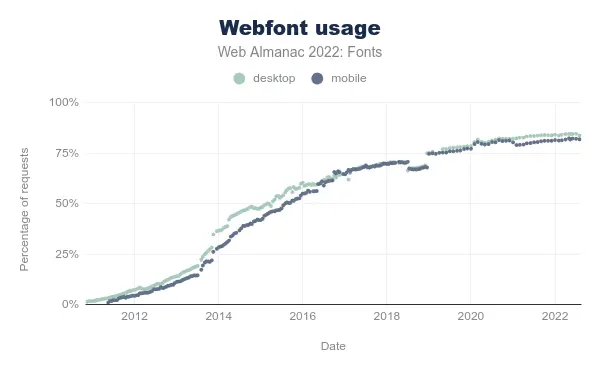

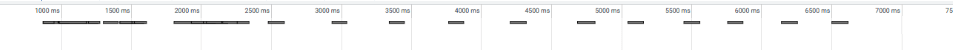

Original requests

Requests after Subset and conversion to woff2

The woff2 format offers an average of 30% more compression than the woff format and even more than other formats like ttf.

This change in format, combined with Subset, reduced the total weight of the fonts from just over 400 kb to just under 90 kb, a reduction of about 78%.

To go further

- Best practices for fonts : overview of the different best practices related to fonts, mainly in order to improve the performance of a website

- Introduction to optimising web fonts: tips and tools for optimizing fonts

- Reduce web font size : different optimization strategies

- Wakamaifondue : a free online tool to analyze what is in a font file

- Font Subsetter: a free online tool to limit the number of characters in a font file.

- Unicode range subsetting : an approach of the Subset based directly on unicode in order to keep only the really used characters.

- Self-hosting explained (including Google Fonts) : how to host fonts yourself

Laurent Devernay Satyagraha has been an expert consultant at Greenspector since 2021. He is also a trainer, speaker and contributor to the W3C’s Web Sustainability Guidelines, INR’s GR491, greenit.fr’s 115 best practices and various working groups, notably around the RGESN.

DOM as a metric for monitoring web sobriety?

Choosing the right metric to assess its impact is critical in a sobriety approach.

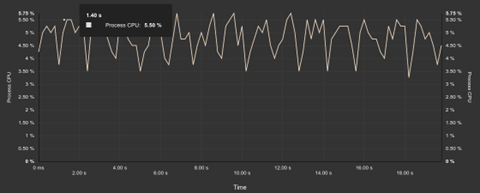

We have validated the use of energy in our tools (https://greenspector.com/fr/pourquoi-devriez-vous-mesurer-la-consommation-energetique-de-votre-logiciel/ and https://greenspector.com/fr/methodologie-calcul-empreinte-environnementale/ for more details). We do however use and measure other metrics such as CPU. This metric can however be complex to measure and some tools or teams use other more technically accessible elements. The CPU is an interesting metric to measure the resource footprint on the terminal side. Indeed, we have carried out measurements on several hundred sites and it is clear that the CPU is the most important metric for analysing the impact of software. This is why all the models that use the data exchanged to calculate the impact of the terminal are not consistent. CPU-based models (such as the Power API) are preferred.

However, it is necessary to be rigorous in the analysis of this metric as there may be interpretation biases (Example of criticism on the CPU). The criticism must be even more important on the way to obtain this metric, and more particularly in the case of modelling the CPU. This is the case, for example, with methods for projecting the CPU into the web from DOM elements.

This is based on the assumption that the structure of the DOM has an impact on the resource consumption of the terminal. The more complex the dom, the more it needs to be processed by the browser, the more resources (CPU and RAM) it uses and the more environmental impact it creates.

Assuming that the hypothesis of a correlation between DOM complexity and environmental impact is valid, the metric often used is the number of elements. A DOM with many elements may be complex but not systematically so. To take into account the complexity of the DOM, it would be necessary to take into account the architecture of the DOM, in particular the depth, the type of node (not all nodes have the same impact on the browser…). The choice of the number of DOM elements is therefore debatable.

But is the choice of DOM complexity a viable assumption? There are several criticisms of this.

The DOM is a raw structure that is not sufficient for the browser to display the page. The style is used with the DOM to create the CSSOM, a complexity of the style can thus greatly impact the CSSOM, even with a simple DOM. Then the layout tree is a structure that will allow the display to be managed (typos, sizes…), this management is much more complex to handle for browsers.

A DOM can be modified after its creation. This is called reflow and repaint. The browser will recalculate the layout and other things. This can happen several times during loading and after loading. The depth of the DOM (and not the number of elements) can influence but not only: the loading and execution of JS code are to be taken into account.

Independently of the DOM, resource consumption can be impacted by various processes on the terminal. In particular, all the JS processing that will be executed when the page is loaded. This cost is currently the main cost on the CPU in the web. And you can have a DOM with 100 elements (not many) and a JS gas factory.

Graphics animations will increase resource consumption without necessarily impacting the DOM. Even if most of this processing is handled by the GPU, the resource impact is not negligible. We can also put in this category the launching of videos, podcasts (and more generally media files) and ads.

There are also many other sources of resource consumption: ungrouped network requests, memory leaks.

The use of the DOM should therefore be used with great care. It is best used as a software quality metric that indicates “clean HTML”. Reducing the number of DOM elements and simplifying the DOM structure may be a good sobriety practice but not a sobriety reduction or CO2 calculation KPI.

Digital Sobriety Expert

Books author «Green Patterns», «Green IT – Gérer la consommation d’énergie de vos systèmes informatiques», …

Speaker (VOXXED Luxembourg, EGG Berlin, ICT4S Stockholm, …)

Green Code Lab Founder, ecodesign software national association

Are we really having a positive impact?

At Greenspector, our mission is to help our customers reduce the environmental impact of their digital services. We work on this every day, but is it enough to offset our own impacts?

To this fundamental question, we must admit that we do not have a simple answer at this time. We will propose to our Mission Committee to work on this subject in order to go further. In the meantime, here is what we can share with you.

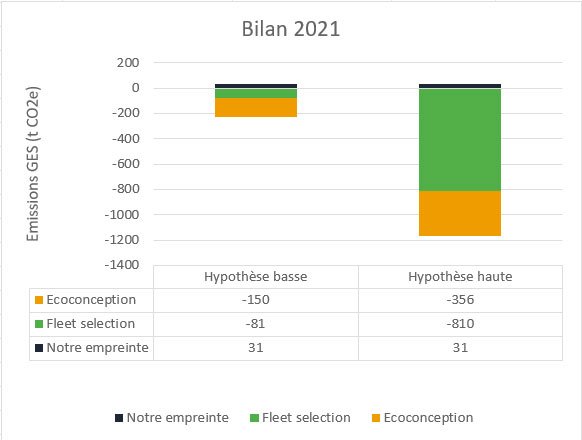

To verify that we are having a positive impact, we need to know our own impacts, and estimate the impacts that our clients are avoiding thanks to us. For this exercise, we will focus on the most easily assessable impact data: greenhouse gas emissions.

Our impacts

This is the “easy” part of the calculation. We have been doing our carbon footprint every year since 2019, using the excellent software from our friends at Toovalu. So we know our greenhouse gas emissions. In 2021, they were 31 tCO2e.

Is this a lot? We can reduce this value to a monetary ratio commonly used in this type of approach: 31 tCO2e for 851 k€ of turnover in 2021, which represents 36.9 kgCO2e/k€ of turnover. By way of comparison, ADEME indicates an average value of 110 kgCO2e/k€ for the category “low material services”. We are therefore 66% below the sector average. This is good, but we can certainly do better.

Avoided impacts

This is where things get complicated. On the one hand, our activities are diverse (sales of licenses, audits of mobile applications or websites, help in choosing Android fleets, etc.). On the other hand, it is not so easy to know how much we have helped to avoid. We need to be able to measure “before” and “after” (which does not always happen) and ideally, between “before” and “after”, only our recommendations to reduce impacts should have been applied. However, if you develop applications or websites, you know that between two versions, it is rare that there are not multiple changes of all kinds.

Finally, there is a methodological question: let’s suppose an audit on a version 1.0, which leads to 30% less impact on a version 1.1. Can we consider that this 30% will be avoided ad vitam aeternam, in other words, can we consider that version 1.7, which will be released in 18 months, will have 30% less impact than 1.7 would have had if we had not intervened on version 1.0? For want of a better answer, we have chosen to consider that the avoided impacts apply for the next 12 months.

So we do not have the possibility of calculating avoided impacts on all our projects or for all our clients – which we regret. However, we can get an idea from a few cases for which this calculation was possible.

Let’s take three examples:

- The SNCF Connect mobile application (Android version): we were able to determine the impact avoided on the TER ticket reservation process: -18.9% or -10 tCO2e over one year.

- At the opposite extreme, the Orange Group’s Integrated Annual Report (IAR): the RAI 2021 website has a 55% lower impact than the RAI 2020, which for its audience – modest for this type of content – represents an avoidance of 0.024 tCO2e over one year.

Here we have 2 projects typical of our activity, extreme in their audiences, accumulating 10 tCO2e avoided, so an average of 5 tCO2e per project. However, in 2021 we worked on more than 70 application or website projects. By taking the average of these two projects, multiplied by 70 projects, we arrive at 356 tCO2e avoided. Another approach based on a categorisation of each service according to its intensity of use gives us 150 tCO2e. Let us retain this lowest value.

As a reminder, our own footprint that year was 31 tCO2e: even if our low value of 150t was still overestimated, it would be very surprising if it turned out to be less than 31t.

“And the third example?”, say those who follow

The third example is a lesser known service in our catalogue. This is our “Fleet Selection” offer, which consists, thanks to our laboratory measurements, of assisting our customers in choosing a smartphone for their business mobile fleet. The measurements and recommendations focus on autonomy criteria, of course, but also on the durability of the terminals (battery life, robustness, etc.) in order to check that they will be able to meet business needs for as long as possible.

In 2021, we helped a client choose the most sustainable device for a fleet of 35,000 smartphones and 5,000 tablets. Thanks to our measurements, he was able to ensure that he chose a model with an expected lifespan of 4 years instead of 3. The manufacturing impact of a smartphone is on average 54 kg CO2e, that of a tablet 108 kgCO2e (values extracted from the Greenspector impact model). Extending this fleet by one year before replacement therefore represents a saving of 810 tCO2e. It can be argued that we are not 100% responsible for this choice. If we attribute even 10% of these 810t to ourselves, this represents 81 tCO2e avoided – compared to the 31t we emit.

Conclusion

We don’t yet know how to quantify our positive impact precisely, and we may never know. But it is important for us to make sure that we do have a positive impact. This 2021 exercise has demonstrated that.

We will continue to work on this assessment of avoided impacts in order to arrive at more accurate results in the future. But even under conservative assumptions, we are confident that our actions are saving greenhouse gas emissions.

In addition, it should be remembered that improving the sobriety of apps has other positive impacts, particularly on the social aspect by enabling people with old and/or low-end terminals to access these digital services that are often indispensable in daily life.

All this makes us proud and strengthens us to continue our mission.

Thomas CORVAISIER is the CEO of GREENSPECTOR. After getting his degree in Engineering he worked for over 15 years in IT consulting alongside major companies, focusing on testing and software quality. He then worked on CSR topics (carbon accounting, environmental management) and eventually mixed these skills into GreenIT expertness and cofounding Greenspector.

Reading grid for environmental commitments of web hosting offers

After a first article where we based ourselves on the websites of the hosting companies to compare the hosting companies proposing “eco-responsible” offers, let’s take a closer look at the offers in question.

The choice of a web hosting service is often complex because of the many factors to be taken into account (security, availability, storage capacity, sovereignty, etc.). If you also want to choose an offer based on its environmental impact, the choice becomes even more complex.

The main objective of this article is to present some criteria to be taken into account when choosing a web hosting offer.

We first look at the existing good practice guidelines.

Once the list of environmental criteria has been established, we will go into more detail on each of the criteria in order to better understand them but also to have the right information to understand the available criteria or even discuss them directly with the hosts.

Indirectly, this reading grid can also be useful for accommodation providers who are concerned about their environmental impact.

Our objective here is to propose a simple reading grid, allowing anyone to understand what to base their choice of an “eco-responsible” host on. However, all this information will not necessarily be on the websites of the hosting companies. The easiest way is to contact these companies directly to get the missing data.

We obviously welcome feedback and constructive comments in order to improve this reading grid and to know how it is used.

Existing benchmarks

In order to better understand how the environmental impacts of accommodation offers are translated, we started by looking at what the existing standards suggest on this subject.

In order to choose an eco-responsible host, the 115 good web design practices propose the following items (see below for details of each):

- Management of WEEE (Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment)

- PUE (Power Usage Effectiveness)/CUE (Carbon Usage Effectiveness)/WUE (Water Usage Effectiveness)

- Responsible purchasing policy

- Respect for the social dimension

- Low carbon energy supply

- Carbon offsetting

The RGESN (Référentiel général d’écoconception de services numériques) proposes a dozen good practices relating to hosting. Among other things, it deals with :

- European Code of Conduct for Energy Efficiency in Data Centres.

- Presence of an environmental impact reduction approach (supporting indicators)

- PUE/CUE/WUE

- Equipment management

- Use of renewable energy

- Fatal heat

- Location of servers

- Good data management practices

Note: most of these criteria can be found in those selected for this comparison, with the exception of those relating to the location of servers (mentioned in the social commitments) or to data management (which depend on usage, in particular according to the criticality of the service and the data).

As usual, the GR491 (Reference Guide to Responsible Digital Service Design) offers many recommendations on the subject. If we stick to the essentials, we find :

- Waste management

- PUE

- Sizing of the physical fleet

- End of life of equipment

- Indicators on the software used

In addition, DINUM (Direction Interministérielle du Numérique) offers a practical guide to responsible digital purchasing, with in particular a sheet on IT infrastructure equipment and hosting services (and hosted solutions). The AGIT (Alliance GreenIT), for its part, updated a white paper in March 2023 on the control and optimisation of the environmental impact of a data centre.

By cross-referencing all these elements, we have drawn up a list of criteria to be checked, which is intended to be complete but not exhaustive.

Note 1: Currently, a working group within W3C is building a set of guidelines for website sustainability. One of the areas of work concerns hosting and infrastructure.

Note 2: In January 2023, the ADEME (Agence de l’Environnement et de la Maîtrise de l’Énergie) published a methodological reference framework for the environmental assessment of hosting and cloud services. This document defines the information to be gathered and displayed. At the time of publication of this article, the companies concerned have not adopted it, but it is hoped that this will be the case in the near future.

Reading grid for the environmental commitments of accommodation providers

Let us now look at what constitutes the reading grid in question.

The criteria used

On the basis of the benchmarks seen above and in order to better evaluate the accommodation offers, the choice was made to base ourselves on several criteria (which we will detail below):

- WEEE Management

- PUE

- WUE

- CUE

- Purchasing policy

- Social commitments

- Management of the heat produced

- Renewable energy supply

- Carbon offsetting

- ISO standards, labels, certificates

Description of the criteria

Management of WEEE (Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment)

How electronic and electrical waste is dealt with. To date, most of this waste is trafficked (What is the status of recycling?).

WEEE management is about extending the life of electronic equipment through recycling or upcycling and reuse. For example, servers used for hosting can sometimes be reused in other contexts.

PUE

The PUE (Power Usage Effectiveness) represents the proportion of energy used to power IT equipment (servers, storage and network) in relation to the total electricity consumed (for cooling, UPS, etc.). It is always greater than 1 and should be as close to 1 as possible. It is estimated that the oldest data centres have a PUE of around 2, whereas the most efficient ones are more like 1.1.

Many structures advertise very low PUE. Here again, it would be important to see how this is calculated. See the Scaleway website: https://www.scaleway.com/fr/leadership-environnemental/

WUE

Following a similar reasoning as for the PUE, the WUE (Water Usage Effectiveness) evaluates the efficient use of water, especially for cooling equipment, by comparing it to the amount of electricity used for the equipment. Indeed, the amount of water used by hosts is very high, which increases the risk of water stress.

The aim is to get as close as possible to zero water consumption per kWh.

Few organisations today report CUE or WUE. However, this type of information is an essential complement to the PUE in order to ensure, for example, that a low PUE is not explained by higher water use.

CUE

Carbon Usage Effectiveness (CUE) compares the amount of greenhouse gas emissions to the amount of electricity used. In order to improve it, technologies with lower CO2 emissions should be selected (which may be the case when a generator is used to produce the electricity rather than using the electricity grid directly). The objective may be to have a UEC of less than 0.1 kg of CO2.

Purchasing policy

The manufacture of equipment remains the most impactful stage in its life cycle, notably because of the many resources (including metals and rare earths) required. The purchasing policy is therefore an essential element in limiting the environmental impact of a hosting company, even if the manufacture of data centre equipment has less impact than its electricity consumption. Thus, some opt for reconditioned equipment or manufacture their own equipment and all must keep in mind the efficiency and durability of the equipment purchased.

Social commitments

It is impossible to make it an objective and directly measurable criterion. However, this category includes what some companies do to reduce the impact of their activity or to contribute to society, which is an essential component of responsible digital. Global elements such as a CSR plan or the Lucie label can testify to this. It may also be interesting to consider the location of buildings as well as local actions, choice of service providers, etc.

Gestion de la chaleur produite

Due to its activity and the demand on its equipment, a hosting company can produce a lot of heat. In order to keep the equipment in working order, it is necessary to cool it down, most often by using electricity via air conditioning for example (hence the notion of PUE seen above) or water. When released directly, this heat can have a negative impact on the environment (sometimes referred to as waste heat or energy). Some accommodation providers therefore use it to heat neighbouring buildings. This can be measured by the Energy Reuse Factor (ERF).

Renewable energy supply

Data centres are often criticised for their electricity consumption. While the priority is to ensure that as little electricity as possible is used, it is important to rely on renewable energy as much as possible to limit the environmental impact. This can be measured by the Renewable Energy Factor (REF).

Most hosting companies are focusing on renewable energy. We have based our analysis on the companies’ statements on the proportion of renewable energy used. By way of comparison, the Green Software Foundation’s approach to this (for their Green Hosting Directory which is mentioned by several of the organisations compared here) is rather simple. They distinguish between but take into account organisations that :

- Use only renewable energy

- Invest in renewable energy to offset their own use of non-renewable energy

- Use carbon offsetting

This choice may be debatable (particularly with regard to the inclusion of carbon offsetting). It is up to each individual to see what he or she deems necessary (in terms of procedures and evidence).

It is also important to distinguish between decarbonised energy (e.g. nuclear) and renewable energy.

Finally, claims of “100% renewable energy” can be misleading. It is therefore up to each individual to find out more directly from the companies.

Carbon offsetting

Carbon offsetting is the final step in the process of reducing environmental impacts. It should only be used when emissions have first been reduced as much as possible through sobriety and efficiency. Moreover, the effectiveness of some carbon offsetting solutions is regularly questioned. As there are several ways of offsetting, it is advisable to approach companies to find out more about the precise nature of their approach. In accordance with the recommendations of ADEME and EcoInfo, the notion of carbon neutrality should be approached with caution and avoided as much as possible.

ISO standards, labels, certificates

We look at a number of elements as a matter of priority. These include ISO50001 (energy management), ISO27001 (information security) and ISO14001 (environmental management). In addition to this, we sometimes find the HDS (Health Data Hosting, which includes ISO27001 and ISO50001 among other standards). Finally, the Code of Conduct on Data Centre Energy Efficiency includes many good practices. Greenethiquette is sometimes mentioned, but has disappeared in favour of more detailed standards (such as the European Code of Conduct).

Conclusion

The notion of an eco-responsible host has been around for several years (notably via the Greenethiquette), but the precise criteria are still under consideration (not to mention what one is entitled to expect from it). Even if some companies are very transparent on their websites (notably via dedicated pages), this cannot replace a more in-depth discussion, both to find out about missing criteria and to better understand the actions already taken. It is therefore to be hoped that hosting companies will move towards concrete criteria to demonstrate their environmental impacts and communicate them in a transparent manner.

For the time being, it is to be hoped that this reading grid will be useful for those who wish to move towards more environmentally friendly accommodation offers, but also so that everyone can be in a position to push companies towards more virtuous actions.

Laurent Devernay Satyagraha has been an expert consultant at Greenspector since 2021. He is also a trainer, speaker and contributor to the W3C’s Web Sustainability Guidelines, INR’s GR491, greenit.fr’s 115 best practices and various working groups, notably around the RGESN.

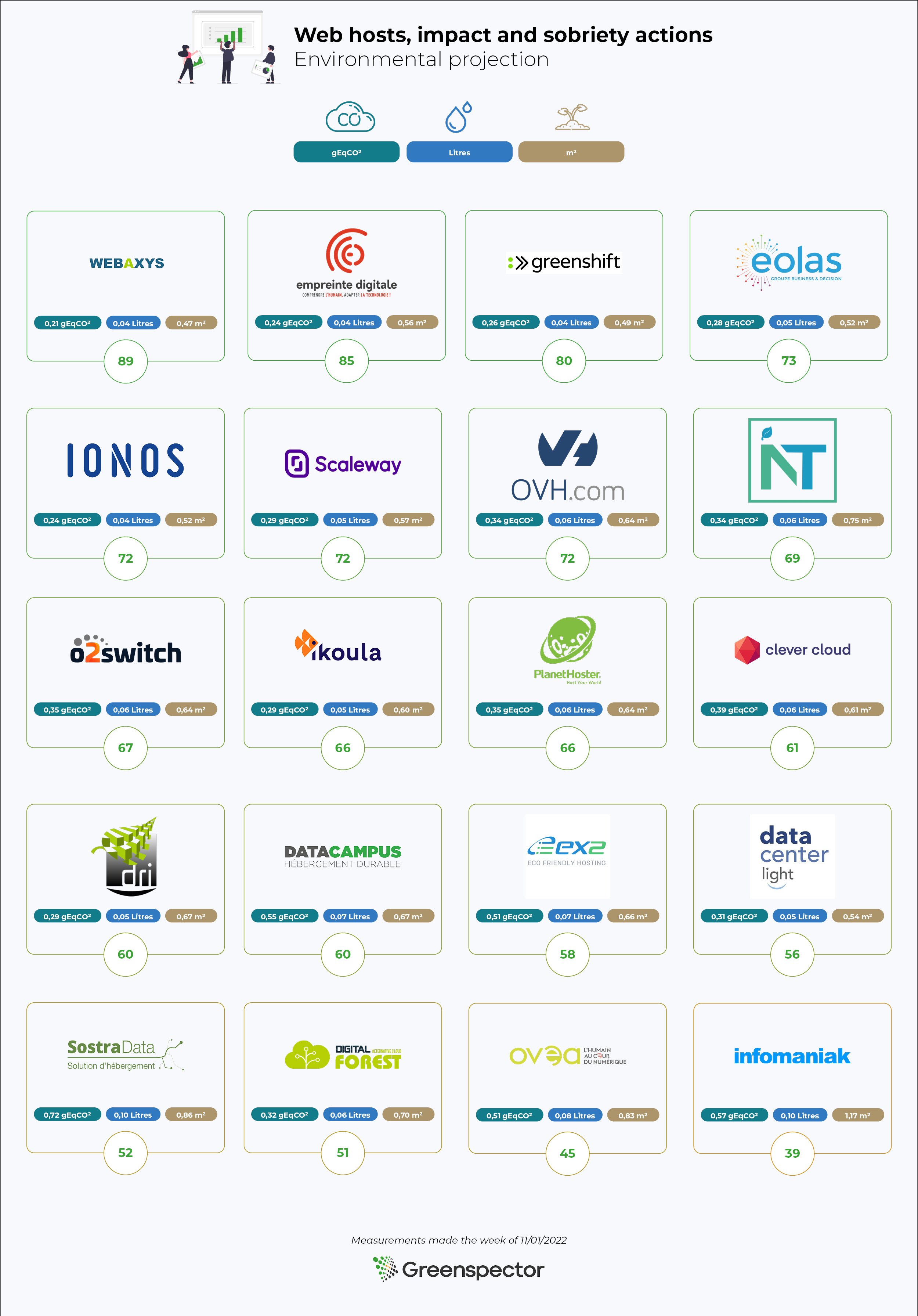

Web hosts, impact and sobriety actions

The article is based on measurements taken in November 2022. It is possible that some companies have since redesigned their websites.

Summary of the article

More and more web hosting providers are claiming to be environmentally friendly.

– We measured the homepage of 21 web hosting providers.

– We analysed the homepage of the first ranked provider, which is Empreinte Digitale (now known as Boscop).

– We then analysed the homepage of the last one in the ranking which is Infomaniak.

– We then took a look at Greenshift’s site by exposing an extract of the HTTP requests of the homepage.

Finally, we reviewed the good practices of sobriety and accessibility which reveal that Eolas and Empreinte Digitale (now known as Boscop) have the fewest accessibility errors unlike Infomaniak which has the most.

In the next article, we will look at the criteria needed to assess the environmental friendliness of a hosting company.

When we are interested in digital sobriety, the question of the host comes up very often. Indeed, this is a very interesting and cross-cutting lever for reducing the environmental impact of digital services. Things get more complicated when you try to sort out the real from the fake in order to choose the best possible host according to the project’s business constraints. Some providers go so far as to talk about carbon neutrality or even carbon negativity.

Claims of carbon neutrality are most often based on the source of the electricity used according to a market-based (supplier’s claims) or location-based (geographical energy mix) approach. Given that some of the scopes 1, 2 and 3 are often neglected, all of this makes these claims invalid. The purpose of this article is not necessarily to go into this point in detail, but you will find some initial answers here:

- [Youtube, 24min 16s] Carbon footprinting tools for public clouds, a presentation by Pierre Rust from Orange Innovation

- Carbon neutrality’ for digital companies, by EcoInfo

Today, in all cases, the claims of eco-responsibility of hosting providers are mostly based on PUE (Power Usage Effectiveness) and the source of the electricity used. This does not seem to be enough. At Greenspector, we decided to look into the subject, to see what was being offered today and to base ourselves on the existing literature in order to determine what criteria to use to choose a hosting company. We were then able to classify several French (or nearby) hosts.

In this first article, we decided to evaluate the homepage of their sites from the point of view of digital sobriety, in order to check whether they reflect their environmental claims. This approach is of course biased and unrepresentative, but it already gives an idea of where each of them stands from this point of view.

It is only with the second article that we will really be able to decide between the hosts, by sifting through the criteria we have chosen.

Comparison of home pages

Based on their intentions regarding environmental impacts, 21 accommodation providers were selected. We have selected as a priority those that show efforts to reduce the environmental impacts of the services they offer. We may have missed some. If so, please let us know!

Based on this list, we measured the homepage of each with the Greenspector tool in order to compare them.

| Nom | URL | Ecoscore | Energie (mAh) | Données transférées (Mo) | Requêtes HTTP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Webaxys | https://webaxys.fr/ | 89 | 4,173192 | 0,47913 | 21 |

| Empreinte Digitale | https://cloud.empreintedigitale.fr/ | 85 | 5,009883 | 0,313111667 | 18 |

| Greenshift | https://www.greenshift.co/fr/ | 80 | 4,253108 | 1,079741667 | 51 |

| Eolas | https://www.eolas.fr/ | 73 | 4,449822 | 1,416203333 | 59 |

| IONOS | https://www.ionos.fr | 72 | 4,586076 | 0,9967127 | 27 |

| Scaleway | https://www.scaleway.com/ | 72 | 5,083758 | 2,247849663 | 29 |

| OVH | https://www.ovhcloud.com/fr/ | 72 | 5,553175 | 1,832020334 | 64 |

| Neutral IT | https://neutral-it.com/ | 69 | 6,62236 | 1,286239 | 49 |

| o2switch | https://www.o2switch.fr/ | 67 | 5,3824 | 0,979763667 | 90 |

| Ikoula | https://www.ikoula.com/ | 66 | 5,315384 | 1,54606967 | 33 |

| PlanetHoster | https://www.planethoster.com/ | 66 | 5,469159 | 1,778474 | 76 |

| DRI | https://www.dri.fr/ | 60 | 5,98907 | 0,451148333 | 27 |

| Datacampus | https://datacampus.fr/ | 60 | 5,691275 | 13,14124667 | 64 |

| EX2 | https://www.ex2.com/ | 58 | 5,474202 | 9,756049 | 91 |

| Data Center Light | https://datacenterlight.ch/ | 56 | 4,686341 | 2,86276037 | 51 |

| Sostradata | https://www.sostradata.fr/ | 52 | 7,235153 | 17,19431033 | 89 |

| Digital Forest | https://digitalforest.fr/ | 51 | 6,225642 | 0,897602 | 35 |

| OVEA | https://www.ovea.com/ | 45 | 7,01255 | 4,253318032 | 111 |

| Infomaniak | https://www.infomaniak.com/ | 39 | 10,30043 | 3,092772997 | 72 |

Résultats des mesures sur les pages d’accueil

Now let’s look in more detail

In terms of the Ecoscore (whose calculation methodology can be found on the Greenspector blog), the Webaxys home page does best and Infomaniak does worst. For Infomaniak, this can be explained by the fact that the energy impact of the site is very high. It is even the highest in the sample. On the other hand, from this point of view, it is once again Webaxys that comes out on top. Empreinte Digitale (now known as Boscop) presents the lowest volume of transferred data while Sostradata transfers the most (more than 17 MB!). Concerning HTTP requests, the home page of Empreinte Digitale (now known as Boscop) uses the least while the one of OVEA has the most (at first sight, some optimizations would be quite easy to implement by avoiding duplicates and by delaying the loading of the chat or even by questioning its relevance).

The home pages of the Webaxys and Empreinte Digitale (now known as Boscop) sites clearly stand out and we will now analyze them in more detail. We will then complete our analysis with a quick look at the elements of the Infomaniak site that make it more impactful. We’ll finish with a brief overview of the other sites.

Empreinte Digitale (now known as Boscop)

This homepage is particularly light, which is an opportunity to note the application of several good practices:

- Optimised and lazy-loaded images

- Third-party services mastered and, in principle, all self-hosted

- Very little JS and CSS

- Use of system fonts only

The site is pleasant and attractive. The score could be even better without the animation but this is absent on mobile. The choice of dithering for some images highlights the desire to produce a site as light as possible but is not necessarily necessary.

Webaxys

We find here light and lazy-loaded images, with a simple and attractive service.

On this type of very optimized and light site, some flaws stand out even more, especially the use of Google fonts.

Here we see 7 requests only for these fonts whereas a system font would probably have been suitable. It should also be remembered that their use from Google servers may pose a problem with respect to the RGPD. A variable font could limit the number of files and a subset (limit to useful characters) could reduce the size. But the priority would be to use a system font.

Finally, the last request of the list is probably FontAwesome. So here we get an icon font while only a few icons are useful (and could be integrated in optimized SVG, maybe even directly in the HTML).

Infomaniak

The Infomaniak site stands out for its low Ecoscore and high energy impact.

If you take a closer look, you’ll notice that most of the weight of the page is due to numerous JS files (about forty in all!).

In addition, the animation at the top of the page (for the search of a domain name) seems to be one of the causes of the overconsumption of energy, highlighted in the Greenspector tool:

Other possible explanations for this over-consumption may be found in JS processing. In any case, it should be analysed and limited.

Other websites

Greenshift’s homepage shows a low energy impact, despite the inclusion of animations when the page is loaded. However, in terms of usability, the presence of horizontal scrolling on mobile phones is not ideal.

For the Sostradata site, which has the highest volume of data transferred in the sample, a quick glance reveals the first areas of improvement:

- Avoid including a Google Maps component directly on the homepage

- Optimise images (size, format, quality, lazy-loading)

Good practice in digital sobriety

In terms of good practice, it is worth noting that the Neutral IT homepage meets the most criteria.

From this point of view, we found that some good practices are almost never implemented on the pages in our sample. To improve impact, one should systematically consider :

- Do not let the browser resize images, this limits the consumption of terminal resources

- Only download the necessary images and do lazy loading

- As far as possible, do not integrate css and js code into HTML files; this will avoid systematically reloading the whole file if necessary

- And of course, once the css and js files are independent, they should be minified to save space

Best practices for accessibility

In addition to measurements and verification of good practices (two complementary approaches that are difficult to separate), we were curious to briefly evaluate the selected sites from the perspective of accessibility. While it is important to reduce the environmental impact of digital services, this cannot be done without ensuring that the site adapts to all contexts of use so as not to exclude anyone. What is the point of having the least impactful site possible if it is unusable for a part of the population?

As we do not wish to be exhaustive, we have relied on the aXe tool (it should be remembered that this type of tool is not intended to cover all the WCAG or RGAA criteria) and on the manual verification of certain criteria (200% zoom, content linearisation, textual alternatives, etc.) In accessibility as in digital sobriety, there is no magic wand!

In the end, our findings are as follows:

- The Eolas and Empreinte Digitale (now known as Boscop) websites have the fewest accessibility errors

- Despite its reduced environmental impact, the Webaxys site has several errors that are fairly easy to fix.

- The Infomaniak site is among the sites with the most errors

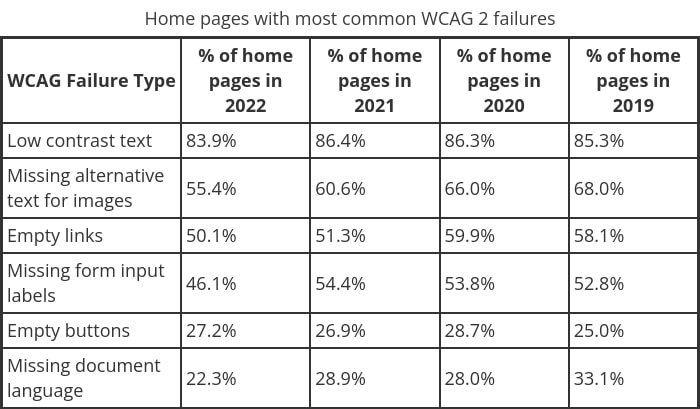

- Among the most frequent errors, we find mainly those highlighted by the WebAIM Million study (which is consistent):

So here we see (once again) that accessibility and digital sobriety are linked. It would be difficult to say that those who do not take care of the sobriety of their websites do not care about accessibility (and vice versa). On the other hand, it is important to remember that it will be all the easier to apply accessibility criteria to a sober site, and even more so when the two approaches are carried out jointly throughout the project’s life cycle.

Conclusion

A first quick analysis of the websites of the selected hosting providers allows us to distinguish those who make the effort to create a sober (and accessible) site. While this does not indicate that they are paying attention to reducing the environmental impact of their hosting offers, it will be interesting to see if the trends noted here are confirmed later.

In the next article in this series, we will look at the criteria needed to assess the environmental responsibility of a web host. We will return to the websites of the selected hosts to see how each one measures up against the criteria in question.

Laurent Devernay Satyagraha has been an expert consultant at Greenspector since 2021. He is also a trainer, speaker and contributor to the W3C’s Web Sustainability Guidelines, INR’s GR491, greenit.fr’s 115 best practices and various working groups, notably around the RGESN.

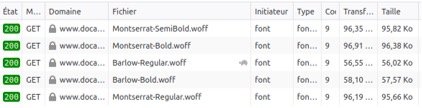

Reducing the impact of autocompletion

When we browse the web, autocompletion is almost everywhere. In particular, this functionality is implemented on search engines, whether they are website-specific or not. So, when the user types in the words they are looking for, suggestions are made dynamically, whether to complete the words or phrases they type in or to display the search results as characters are added.

In the case of Google, these suggestions are often derided as incongruous. Not to mention the SEO chestnut about the death of the search engine.

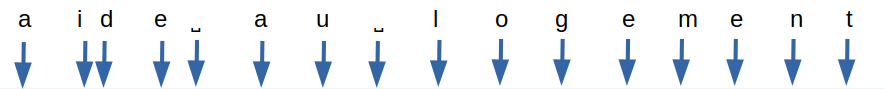

Take the example of the Google search engine:

Here, the blue arrows represent character inputs and the black rectangles represent autocomplete queries.

We arrive at a total of 16 XHR type queries for 5.1 kb transferred.

The number of queries remains the same whether the input is fast (input in 2 seconds for the whole search) or longer (7 seconds in total for the input).

Autocompletion can also be found in some input forms, to ensure that the text entered corresponds to what is expected (city, country, etc).

While this mechanism can be an aid to the user, the environmental impact of the queries generated should not be overlooked. Let’s see how to limit them.

First recommendations

If sobriety is a priority, the best thing to do is not to integrate an autocomplete mechanism. However, input help is a definite advantage for users in most cases.

In the case of forms, the GreenIT.fr collective’s collection of 115 good practices in web ecodesign recommends input assistance. In this way, less strain is placed on the server while ensuring that the text entered remains consistent with what is expected.

On the GR491 side, there are two recommendations:

- Limit unnecessary searches by local search engines: this is based on the number of letters entered in order to space out the queries

- Limit the number of requests between the client and the server: this more general good practice applies perfectly here

Rather than systematically implementing autocompletion and search, it is sometimes possible to make filters (and sorting mechanisms) available to the user.

With these initial elements in mind, let’s look at how we can go even further.

Recommendations

Ensure that requests are as light as possible

When the client sends a request to the server, ensure that it contains only the elements necessary to provide a relevant response.

When the server sends a response, again ensure that :

- Only relevant fields are returned. For example, it is not always necessary to display an image for each result

- Only the necessary elements are returned (relevance of responses and pagination of results)

Do not offer autocompletion before a few characters

Before launching the first query, it is preferable to wait until 5 characters have been entered or at least 2 seconds have elapsed since the last entry by the user.

This avoids returning results for a request that is too vague (when the number of characters entered is insufficient), while taking into account the case where the term searched for is deliberately short (“summer”, etc).

Spacing out the queries in time

After the initial query, wait until 3 new characters have been entered or at least 2 seconds have elapsed since the last query.

Limit the number of queries for fast entries

In addition to the previous rule, in the case of fast input, wait at least one second between each request. Indeed, some particularly fast users can enter a character every 200 ms.

Measuring local relevance

When a user adds characters to his search, the results become more precise and their number decreases. It is possible to perform this filtering directly locally, without additional requests to the server. For example, if results were obtained for “housing assistance”, it is possible to filter on the client side if the user continues by typing “housing assistance”.

This good practice is particularly relevant in the case of an input field in a form. For example, when entering a city or country, the elements of an initial query can be refined locally as the user continues to type.

Be aware that if a space is entered and new terms are added, the logic chosen for the search results must be taken into account. In particular, should a result contain all the terms entered or only some of them?

Be careful also to take into account the case where the user deletes some of the characters entered. You may also want to temporarily store the queries you have already made so that you can use them again if necessary.

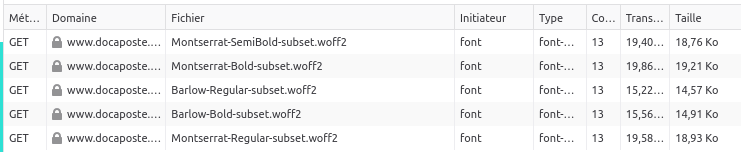

Back to the example of the Google search engine

Taking the case of the Google search engine mentioned at the beginning of the article (16 queries, 5.1 KB transferred), we arrive at 3 queries in total for 1 KB transferred.

- A first query only performed when at least 5 characters have been entered.

- A second query when 3 more characters have been entered.

- A third query when 3 more characters have been entered.

- The local evaluation of the results to be returned at the end of the input, since it is only a question of filtering the results obtained following the third query.

Conclusion

If autocompletion is a necessity and assisted input is not possible, the following good practices should be implemented:

- Ensure that queries are as light as possible

- Do not offer autocompletion before a few characters

- Spacing out queries over time

- Limit the number of queries for quick entries

- Measure relevance locally

Finally, although this input help may be beneficial to many users, do not neglect its accessibility.

Laurent Devernay Satyagraha has been an expert consultant at Greenspector since 2021. He is also a trainer, speaker and contributor to the W3C’s Web Sustainability Guidelines, INR’s GR491, greenit.fr’s 115 best practices and various working groups, notably around the RGESN.

Deleting emails is useless, working on sober email solutions is mandatory

The discovery that digital technology was not so virtual and that it could have an impact on the environment brought a multitude of injunctions followed by a multitude of criticisms and counter-injunctions. “You have to delete your e-mails”, “No, it’s like peeing in the shower, it’s useless”… The criticism of these actions by the digital actors is quite strong relative to the large part of the “non-technical” population that took this to heart (and increased its eco-anxiety!).

These discussions have also led to a decision on which is the most polluting between use and manufacture. Use of the mail versus manufacture of the terminal on which the mail was read. The latter being announced as more impacting, this was in the sense of uselessness to optimize the mail part!

Yes, the impact is concentrated on the manufacturing of the terminals. Yes, the unit impact of an email is low, especially compared to a raclette (this is a private joke, a joke that circulates among the detractors of digital sobriety). These are quite reassuring messages in a binary world. Reassuring to limit eco-anxiety. But mostly reassuring for the digital actors to not deal with the problem and continue business-as-usual.

Because yes, there is a potential problem. Because of the scale effect, a low unit impact can lead to a high global impact with a large number of users and more and more uses. The 4% impact of digital technology does not just happen. Especially when you list and observe what happens on the internet every minute https://www.allaccess.com/merge/archive/32972/infographic-what-happens-in-an-internet-minute. A diversity and a frequency much more important than raclette (for information, we should eat raclette 12 times a year https://journal-des-etudes.com/selon-la-science-il-faudrait-manger-de-la-raclette-12-fois-par-an/ )

The plastic packaging of our food, taken individually, does not have a huge impact. A few milligrams of plastic. But plastic is indeed a global environmental problem. As Gerry McGovern would say, plastic is an environmental plague but if you have a plastic bag, use it! https://gerrymcgovern.com/books/world-wide-waste/exploding-plastic-inevitable/

“Avoid plastic packaging. Bring your own bag and avoid the barcodes. Whenever you can replace plastic with another material, do, but don’t replace it simply for the sake of it. If you have a plastic bag, use the hell out of it.”

As a digital player, we need to work on impacts because the effect of scale means that our solutions have a significant global impact. Using the “order of magnitude” argument by taking only the unit impact is not valid.

Behind an email, there is a solution provider. Behind a social network, too. Each digital actor contributes to a brick that is ultimately used by a user.

It is therefore necessary to optimize our solutions, to offer better management of solutions. What about smart email deletion options that would be proposed in email solutions? What about providing solutions to help writing sober emails (attachments, signatures…)? It is possible, editors have done it for spam management, why not go further?

As for user awareness, it is necessary but it must be less anxiety-provoking, without becoming whataboutism (https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whataboutism).

Digital Sobriety Expert

Books author «Green Patterns», «Green IT – Gérer la consommation d’énergie de vos systèmes informatiques», …

Speaker (VOXXED Luxembourg, EGG Berlin, ICT4S Stockholm, …)

Green Code Lab Founder, ecodesign software national association

Digital Sobriety Requirements for Cities and Communities – Ranking

In 2020, we published a study on digital sobriety requirements in public procurement. With the publication this summer of the decree n° 2022-1084 of July 29, 2022, we thought it would be a good idea to take stock of the sites of cities and communities.

This decree concerns municipalities and communities of more than 50,000 inhabitants, requiring them to develop a responsible digital strategy focusing in particular on reducing the environmental footprint of digital.

We therefore remeasured the sites of the 29 cities and 17 metropolises already discussed in order to compare the results obtained.

The measurements here only concern the first page of each site. Ideally, a larger sample of pages should be taken into account, or even compared on the basis of a user path common to all these sites. However, this approach already allows us to establish points of comparison and to identify some good practices.

Metropolitan sites

The Ecoscore as defined by Greenspector allows a good overview of each site. We will therefore start by looking at its evolution between the initial measurements and the re-measurements.

In most cases, there is an improvement (even slight) in the EcoScore. The cities of Brest, Grenoble, Nice, Orleans and Strasbourg stand out with a very strong increase. For some cities, the trend is downward.

While Nancy had the best EcoScore (74), Rennes takes the lead with an EcoScore of 80.

However, it can be estimated that it would be important for each city to obtain an EcoScore of at least 50/100, which is still not the case for some.

Estimating the environmental impacts of different sites is another good basis for comparison.

We note here that the trend is globally upward for the measured sites with sometimes a strong difference between the initial measurement and the remeasurement. The case of the Saint-Etienne metropolis illustrates this very well.

Further analysis of selected sites

This site appears very light. The images, even if they are rather numerous, are light but should be lazy-loaded (load them only when they are displayed). The use of a variable font would limit the requests. The carousel on the home page does not bring much. The fact that it is in autoplay may lead to overconsumption in addition to potentially causing accessibility problems. The Accessibility page would be more relevant if it stated the compliance with the RGAA (Référentiel Général d’Amélioration de l’Accessibilité) and presented the multi-year accessibility plan for the site. The few animations, even if they are not intrusive, seem superfluous and can lead to overconsumption.

Following the remeasurement, the site of the metropolis of Montpellier is the least well placed. Leaving the site open, we quickly observe more than 300 HTTP requests for more than 30 MB of transferred data. Even after the site is loaded, the requests continue to accumulate.

The homepage is particularly heavy, especially in terms of content: lots of images, autoplay carousels, lots of third-party services.

If quick gains are possible through technical optimization, in-depth work is required, particularly through a more sober approach to design.

Summary of measures for metropolitan websites

| version | Métropoles | ecoscore | Energie | CPU | Données | Mémoire | Requêtes | Carbon | Eau | Sol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| https://metropole.rennes.fr/ - Remesure | Rennes | 80 | 4,60 | 0,83 | 2,22 | 687,58 | 43 | 0,30 | 0,048 | 0,528 |

| https://www.lillemetropole.fr/ - Remesure | Lille | 76 | 4,77 | 0,68 | 2,37 | 685,11 | 24 | 0,28 | 0,047 | 0,537 |

| https://www.grandnancy.eu/accueil/ | Nancy | 74 | 3,54 | 0,58 | 1,35 | 544,09 | 45 | 0,24 | 0,038 | 0,412 |

| https://www.bordeaux-metropole.fr/ - Remesure | Bordeaux | 72 | 4,78 | 0,66 | 1,45 | 756,86 | 51 | 0,30 | 0,049 | 0,551 |

| https://www.grandnancy.eu/accueil/ - Remesure | Nancy | 72 | 4,89 | 0,60 | 2,04 | 718,18 | 42 | 0,31 | 0,050 | 0,560 |

| https://www.orleans-metropole.fr/ - Remesure | Orleans | 71 | 5,69 | 1,46 | 1,77 | 544,13 | 37 | 0,33 | 0,055 | 0,643 |

| https://www.metropolegrandparis.fr/fr - Remesure | Paris | 70 | 4,47 | 0,54 | 2,07 | 704,63 | 38 | 0,28 | 0,046 | 0,511 |

| https://www.saint-etienne-metropole.fr/ | Saint Etienne | 70 | 3,75 | 0,53 | 3,80 | 426,20 | 89 | 0,36 | 0,049 | 0,463 |

| https://www.lillemetropole.fr/ | Lille | 69 | 3,57 | 0,63 | 1,73 | 560,04 | 46 | 0,25 | 0,039 | 0,416 |

| https://www.metropole-rouen-normandie.fr/ - Remesure | Rouen | 66 | 5,00 | 1,30 | 0,94 | 706,73 | 30 | 0,27 | 0,047 | 0,563 |

| https://www.bordeaux-metropole.fr/ | Bordeaux | 62 | 3,87 | 0,85 | 1,34 | 562,92 | 60 | 0,27 | 0,043 | 0,457 |

| https://metropole.nantes.fr/ - Remesure | Nantes | 62 | 5,32 | 1,35 | 10,16 | 748,48 | 60 | 0,52 | 0,067 | 0,626 |

| https://www.clermontmetropole.eu/accueil/ - Remesure | Clermont | 61 | 5,70 | 0,88 | 5,68 | 808,34 | 91 | 0,49 | 0,069 | 0,679 |

| https://metropole.rennes.fr/ | Rennes | 60 | 4,31 | 1,93 | 1,23 | 639,53 | 43 | 0,27 | 0,044 | 0,495 |

| https://www.toulouse-metropole.fr/ - Remesure | Toulouse | 60 | 4,75 | 0,91 | 2,49 | 698,46 | 71 | 0,35 | 0,053 | 0,560 |

| https://www.metropolegrandparis.fr/fr | Paris | 59 | 4,08 | 0,83 | 1,94 | 567,65 | 43 | 0,27 | 0,043 | 0,471 |

| https://www.saint-etienne-metropole.fr/ - Remesure | Saint Etienne | 57 | 5,86 | 1,08 | 34,99 | 819,96 | 104 | 1,13 | 0,113 | 0,743 |

| https://www.brest.fr - Remesure | Brest | 56 | 5,33 | 1,25 | 3,87 | 723,99 | 142 | 0,51 | 0,070 | 0,664 |

| https://metropoletpm.fr/ - Remesure | Toulon | 54 | 5,42 | 0,79 | 4,97 | 686,44 | 176 | 0,58 | 0,078 | 0,694 |

| https://metropole.nantes.fr/ | Nantes | 52 | 5,07 | 1,52 | 8,75 | 699,17 | 88 | 0,52 | 0,067 | 0,613 |

| https://www.ampmetropole.fr/ | Aix Marseille Provence | 51 | 4,38 | 0,91 | 14,12 | 893,42 | 140 | 0,68 | 0,076 | 0,573 |

| https://www.metropole-dijon.fr/ - Remesure | Dijon | 51 | 6,08 | 2,08 | 3,51 | 657,43 | 70 | 0,43 | 0,066 | 0,706 |

| https://www.nicecotedazur.org/ - Remesure | Nice | 50 | 5,02 | 1,21 | 3,06 | 654,93 | 129 | 0,46 | 0,065 | 0,622 |

| https://www.metropole-rouen-normandie.fr/ | Rouen | 49 | 4,37 | 2,93 | 1,64 | 657,77 | 26 | 0,25 | 0,042 | 0,493 |

| https://www.clermontmetropole.eu/accueil/ | Clermont | 45 | 4,31 | 1,49 | 1,23 | 698,79 | 89 | 0,33 | 0,051 | 0,520 |

| https://tours-metropole.fr/ | Tours | 44 | 4,64 | 1,76 | 2,85 | 778,26 | 67 | 0,35 | 0,052 | 0,547 |

| https://tours-metropole.fr/ - Remesure | Tours | 44 | 4,89 | 1,07 | 5,43 | 663,20 | 0,32 | 0,049 | 0,542 | |

| https://www.strasbourg.eu/ - Remesure | Strasbourg | 43 | 6,19 | 2,68 | 2,80 | 754,16 | 84 | 0,44 | 0,068 | 0,725 |

| https://www.grenoblealpesmetropole.fr/ - Remesure | Grenoble | 41 | 6,59 | 2,37 | 3,81 | 696,83 | 86 | 0,48 | 0,073 | 0,771 |

| https://metropoletpm.fr/ | Toulon | 41 | 4,21 | 0,95 | 4,58 | 921,88 | 242 | 0,62 | 0,077 | 0,598 |

| https://www.toulouse-metropole.fr/ | Toulouse | 41 | 4,19 | 1,40 | 2,10 | 601,40 | 70 | 0,32 | 0,048 | 0,498 |

| https://www.ampmetropole.fr/ - Remesure | Aix Marseille Provence | 40 | 7,86 | 2,30 | 10,18 | 840,47 | 207 | 0,84 | 0,110 | 0,984 |

| https://www.metzmetropole.fr/ - Remesure | Metz | 38 | 11,06 | 3,24 | 8,47 | 925,30 | 149 | 0,85 | 0,126 | 1,300 |

| https://www.montpellier3m.fr/ - Remesure | Montpellier | 32 | 5,93 | 2,13 | 40,93 | 754,01 | 259 | 1,48 | 0,144 | 0,843 |

| https://www.brest.fr | Brest | 31 | 5,38 | 2,40 | 3,64 | 882,16 | 218 | 0,61 | 0,081 | 0,711 |

| https://www.metropole-dijon.fr/ | Dijon | 28 | 5,88 | 6,31 | 6,48 | 630,14 | 77 | 0,49 | 0,069 | 0,692 |

| https://www.orleans-metropole.fr/ | Orleans | 28 | 6,40 | 7,57 | 2,27 | 590,65 | 112 | 0,47 | 0,073 | 0,762 |

| https://www.metzmetropole.fr/ | Metz | 26 | 16,10 | 5,97 | 9,20 | 856,20 | 164 | 1,10 | 0,171 | 1,858 |

| https://www.nicecotedazur.org/ | Nice | 24 | 4,62 | 3,05 | 4,28 | 651,05 | 121 | 0,46 | 0,062 | 0,576 |

| https://www.grenoblealpesmetropole.fr/ | Grenoble | 19 | 10,16 | 7,54 | 5,87 | 656,85 | 96 | 0,68 | 0,107 | 1,168 |

| https://www.montpellier3m.fr/ | Montpellier | 19 | 6,39 | 3,44 | 28,83 | 831,25 | 380 | 1,42 | 0,148 | 0,942 |

| https://www.strasbourg.eu/ | Strasbourg | 9 | 7,85 | 8,80 | 1,98 | 675,41 | 0,37 | 0,068 | 0,860 |

We have calculated the average of these data. On the general level we notice that the average ecoscore is 50, the energy consumed is 5,65 mAh, the percentage of CPU used is 2,16, the data exchanged is 6,25 MB, the RAM used is 704 MB, the number of requests is 103. Concerning the environmental impact we can observe that the carbon impact is 0,51 gEqCO2, the water footprint is 0,070 Liters and the soil footprint is 0,68 m2.

By distinguishing the measurements from the remeasurements here are the averages that we obtain:

| Ecoscore | Energie | CPU | Données | Mémoires | Requêtes | Impact Carbon (gEqCO2) | Empreinte Eau (Litres) | Empreinte sol (m2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moyennes des remesures | 57 | 5.72 | 1.40 | 7.30 | 725 | 95 | 0.52 | 0.071 | 0.68 |

| Moyennes des mesures initiales | 43 | 5.57 | 2.92 | 5.20 | 682 | 111 | 0.49 | 0.069 | 0.67 |

City websites

Here again, we start by looking at the EcoScore of the sites of the cities in the sample.

Even more than for the metropolises, the trend for the EcoScore is clearly upward.

In addition to the site of the city of Rennes (already discussed in the context of metropolises), the sites of the cities of Le Havre, Lille and especially Strasbourg have improved significantly. It is also the site of the city of Rennes that presents the best EcoScore. We note in passing the interesting choice of having the same site for the city and the metropolis. As for the lowest EcoScore, it goes to the site of the city of Tours.

Now let’s look at the environmental footprint of these sites.

The overall trend is downward, which is a very good thing.

Further analysis of selected sites

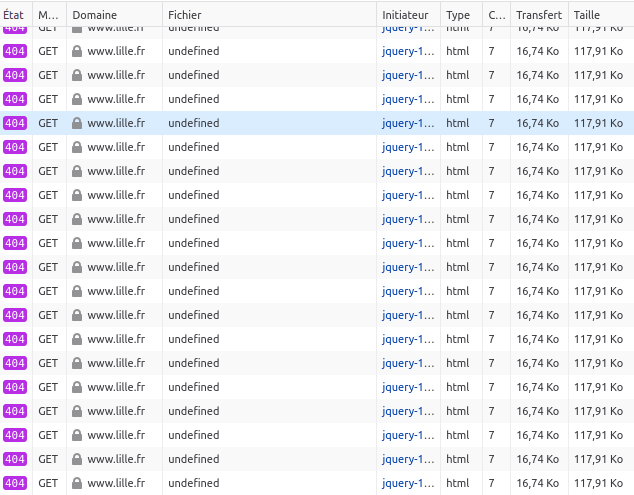

Even if this site has evolved well since the first measurements, there are still areas of improvement to explore.

Many HTTP requests, several MB of data exchanged and some 404 errors among the resources to recover.

We note here in passing the interest of having an HTML 404 page as light as possible because this is often what the server will return if it does not find what is requested. Note that it is possible to modify this via the server configuration in order to send a simple message instead. The best thing is of course to make sure that you don’t go looking for elements that cannot be found.

The homepage is very busy, with an auto-scrolling carousel and many images and content. Il serait avantageux d’utiliser une font variable et d’éviter de charger toutes les icônes de FontAwesome. Some images, weighing several hundred kb, should be optimized.

In a rather classical way, there are many images here, some of which should be optimized.

However, at first glance, the home page does not seem so busy. It is therefore necessary to dig a little to better understand what makes the site so heavy.

We find about ten queries for fonts and we note in passing Google fonts (which can, let’s remember, cause concern with respect to the RGPD).

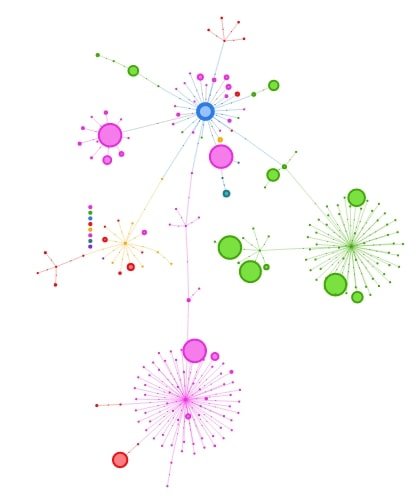

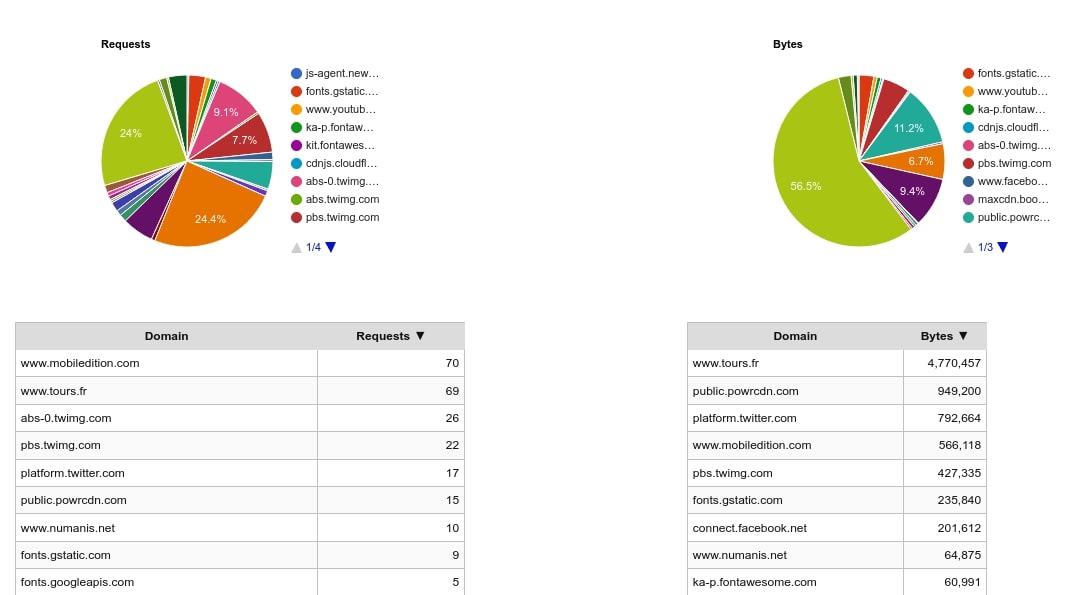

Several requests also seem to correspond to video. But most of the requests come from JS and CSS files. A closer look at the domains of origin of the requests reveals one of the explanations for the weight of the site. A closer look at the domains of origin of the requests reveals one of the explanations for the weight of the site.

This firework is provided by the RequestMap tool developed by Simon Hearne (already mentioned during the analysis of requests from an Android application). If we don’t have the details, we can see that there are many requests and that most of them come from other domains.

The Domains tab of Webpagetest allows us to learn a little more:

This is only an excerpt but it shows several interesting elements:

Most of the requests (in terms of numbers but also in terms of weight) come from other domains

Most requests came from mobiledition.com

Mobiledition.com proposes to those whose site is not responsive to generate a version of their site specially thought for a display on mobile. The intention is not bad but the approach is rather aberrant from the point of view of ecodesign. Indeed, this overlay will exist on top of the original site and will be automatically refreshed at each update of the site. Nearly 10 years after the appearance of the notion of responsive design, it would be important that all sites can adapt to different devices or even that they are thought mobile-first (first for mobile and then extend to other media). Or even offline-first in order to be able to cope more easily with degraded connections.

In summary, it would be important to rethink the site in order to limit as much as possible the use of third party services to make it less impactful.

Measurement results for the cities’ websites

| version | Villes | ecoscore | Energie | CPU | Données | Mémoire | Requêtes | Carbon | Eau | Sol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| https://metropole.rennes.fr/ - remesure | Rennes | 82 | 4,72 | 1,01 | 2,20 | 638,77 | 43 | 0,30 | 0,048 | 0,541 |

| http://www.lemans.fr/ - remesure | Le Mans | 76 | 4,65 | 0,64 | 2,01 | 686,57 | 71 | 0,33 | 0,051 | 0,549 |

| https://www.lille.fr/ - remesure | Lille | 76 | 4,99 | 1,07 | 4,35 | 688,68 | 80 | 0,41 | 0,059 | 0,594 |

| http://www.bordeaux.fr/ - remesure | Bordeaux | 75 | 4,45 | 0,54 | 0,51 | 612,36 | 26 | 0,23 | 0,041 | 0,500 |

| https://www.lemans.fr/ - remesure | Le Mans | 75 | 4,91 | 0,75 | 2 | 737,59 | 71 | 0,34 | 0,054 | 0,577 |

| https://www.reims.fr/ - remesure | Reims | 71 | 5,39 | 1,22 | 2,70 | 695,55 | 61 | 0,36 | 0,057 | 0,625 |

| https://clermont-ferrand.fr/ - remesure | Clermont Ferrand | 68 | 5,34 | 1,12 | 1,11 | 596,62 | 56 | 0,32 | 0,054 | 0,615 |

| http://www.bordeaux.fr/ | Bordeaux | 66 | 3,38 | 1,78 | 0,42 | 486,05 | 93 | 0,28 | 0,04 | 0,42 |

| https://www.amiens.fr/ - remesure | Amiens | 64 | 5,64 | 0,71 | 2,67 | 871,97 | 48 | 0,35 | 0,057 | 0,645 |

| https://www.lehavre.fr/ - remesure | Le Havre | 63 | 5,06 | 1,24 | 4,32 | 775,82 | 88 | 0,42 | 0,061 | 0,606 |

| https://www.lemans.fr/ | Le Mans | 63 | 3,73 | 0,71 | 3,77 | 623,83 | 64 | 0,33 | 0,05 | 0,45 |

| https://www.aixenprovence.fr/ - remesure | Aix | 62 | 5,16 | 0,74 | 5,16 | 748,06 | 108 | 0,47 | 0,065 | 0,629 |

| http://nice.fr/ - remesure | Nice | 62 | 5,40 | 1,33 | 24,73 | 697,57 | 65 | 0,83 | 0,088 | 0,658 |

| https://www.paris.fr/ - remesure | Paris | 62 | 6,00 | 1,85 | 6,81 | 718,24 | 47 | 0,45 | 0,066 | 0,690 |

| https://www.lyon.fr/ - remesure | Lyon | 61 | 4,92 | 0,95 | 3,46 | 740,146 | 114 | 0,44 | 0,062 | 0,603 |

| https://www.paris.fr/ | Paris | 59 | 4,19 | 2,45 | 17,64 | 604,00 | 49 | 0,62 | 0,07 | 0,51 |

| http://www.lemans.fr/ | Le Mans | 58 | 4,08 | 1,96 | 2,75 | 563,91 | 66 | 0,32 | 0,05 | 0,48 |

| https://metropole.nantes.fr/ - remesure | Nantes | 58 | 5,35 | 1,31 | 10,10 | 740,88 | 60 | 0,52 | 0,067 | 0,630 |

| https://www.saintdenis.re/ - remesure | Saint Denis | 58 | 5,77 | 0,87 | 5,54 | 715,67 | 67 | 0,45 | 0,065 | 0,673 |

| https://www.toulouse.fr/ - remesure | Toulouse | 57 | 5,07 | 0,91 | 2,91 | 742,45 | 103 | 0,41 | 0,061 | 0,613 |

| https://www.nimes.fr/ - remesure | Nimes | 56 | 5,44 | 1,55 | 12,29 | 700,41 | 115 | 0,64 | 0,079 | 0,673 |

| https://www.saintdenis.re/ | Saint Denis | 56 | 4,45 | 2,78 | 2,74 | 592,78 | 41 | 0,30 | 0,05 | 0,51 |

| https://www.villeurbanne.fr/ - remesure | Villeurbanne | 55 | 5,28 | 1,13 | 11,97 | 625,22 | 79 | 0,58 | 0,072 | 0,635 |

| https://www.amiens.fr/ | Amiens | 54 | 4,02 | 1,68 | 2,22 | 734,33 | 59 | 0,30 | 0,05 | 0,47 |

| http://www.angers.fr/ - remesure | Angers | 54 | 5,19 | 1,28 | 2,16 | 596,79 | 62 | 0,34 | 0,05 | 0,603 |

| https://www.marseille.fr/ | Marseille | 53 | 4,76 | 1,74 | 7,86 | 402,54 | 243 | 0,71 | 0,09 | 0,66 |

| https://www.reims.fr/ | Reims | 53 | 3,97 | 1,42 | 1,29 | 507,91 | 82 | 0,31 | 0,05 | 0,48 |

| https://toulon.fr/ - remesure | Toulon | 53 | 5,42 | 0,65 | 4,94 | 945,61 | 153 | 0,54 | 0,074 | 0,682 |

| https://www.brest.fr/ - remesure | Brest | 52 | 5,30 | 1,35 | 3,72 | 733,54 | 142 | 0,50 | 0,069 | 0,661 |

| https://www.dijon.fr/ | Dijon | 51 | 4,32 | 2,37 | 4,19 | 580,40 | 91 | 0,40 | 0,06 | 0,53 |

| https://metropole.nantes.fr/ | Nantes | 50 | 6,39 | 2,85 | 12,60 | 656,37 | 62 | 0,62 | 0,08 | 0,75 |

| https://www.montpellier.fr/ - remesure | Montpellier | 49 | 6,27 | 1,01 | 9,45 | 1029,02 | 73 | 0,56 | 0,076 | 0,737 |

| https://metropole.rennes.fr/ | Rennes | 49 | 4,42 | 2,89 | 1,85 | 616,47 | 48 | 0,29 | 0,05 | 0,51 |

| https://www.marseille.fr/ - remesure | Marseille | 48 | 5,92 | 1,71 | 19,55 | 690,65 | 201 | 0,94 | 0,105 | 0,782 |

| https://www.lyon.fr/ | Lyon | 46 | 4,62 | 2,85 | 2,69 | 573,40 | 68 | 0,35 | 0,05 | 0,55 |

| https://www.annecy.fr/ - remesure | Annecy | 45 | 5,57 | 1,79 | 4,23 | 692,91 | 116 | 0,48 | 0,069 | 0,67 |

| https://clermont-ferrand.fr/ | Clermont Ferrand | 45 | 5,03 | 1,76 | 3,17 | 462,48 | 88 | 0,40 | 0,06 | 0,60 |

| https://www.mairie-perpignan.fr - remesure | Perpignan | 45 | 7,33 | 2,41 | 9,74 | 793,54 | 159 | 0,73 | 0,097 | 0,900 |

| https://www.strasbourg.eu/ - remesure | Strasbourg | 43 | 6,38 | 3,14 | 2,79 | 702,44 | 84 | 0,44 | 0,069 | 0,746 |

| http://www.angers.fr/ | Angers | 42 | 5,59 | 4,35 | 3,46 | 591,16 | 57 | 0,39 | 0,06 | 0,64 |

| https://www.dijon.fr/ - remesure | Dijon | 42 | 4,66 | 1,00 | 1,44 | 656,469 | 0,22 | 0,041 | 0,511 | |

| https://www.grenoble.fr/ - remesure | Grenoble | 40 | 6,08 | 2,16 | 6,44 | 571,02 | 73 | 0,49 | 0,070 | 0,712 |

| https://www.mairie-perpignan.fr | Perpignan | 40 | 5,19 | 2,78 | 2,50 | 544,38 | 147 | 0,48 | 0,07 | 0,65 |

| https://www.aixenprovence.fr/ | Aix | 39 | 4,61 | 1,68 | 7,84 | 768,69 | 110 | 0,51 | 0,07 | 0,57 |

| https://www.lille.fr/ | Lille | 39 | 6,23 | 3,39 | 12,66 | 852,37 | 84 | 0,65 | 0,08 | 0,74 |

| https://www.limoges.fr/fr - remesure | Limoges | 39 | 8,51 | 1,82 | 2,33 | 609,38 | 100 | 0,54 | 0,088 | 0,986 |

| https://www.toulouse.fr/ | Toulouse | 38 | 4,57 | 2,44 | 3,00 | 641,75 | 123 | 0,43 | 0,06 | 0,57 |

| https://www.tours.fr/ - remesure | Tours | 38 | 5,68 | 0,88 | 5,67 | 818,58 | 0,35 | 0,055 | 0,628 | |

| https://toulon.fr/ | Toulon | 37 | 5,85 | 2,09 | 16,48 | 923,89 | 215 | 0,90 | 0,10 | 0,78 |

| https://www.brest.fr/ | Brest | 34 | 5,77 | 3,09 | 3,40 | 843,12 | 209 | 0,61 | 0,08 | 0,75 |

| https://www.grenoble.fr/ | Grenoble | 33 | 5,66 | 6,55 | 5,93 | 600,86 | 60 | 0,45 | 0,06 | 0,66 |

| http://nice.fr/ | Nice | 33 | 6,07 | 4,65 | 26,59 | 627,28 | 194 | 1,09 | 0,12 | 0,80 |

| https://www.villeurbanne.fr/ | Villeurbanne | 33 | 5,22 | 2,27 | 8,72 | 740,51 | 128 | 0,58 | 0,07 | 0,65 |

| https://www.lehavre.fr/ | Le Havre | 32 | 4,66 | 3,30 | 5,40 | 726,97 | 106 | 0,46 | 0,06 | 0,57 |

| https://www.montpellier.fr/ | Montpellier | 30 | 5,08 | 1,86 | 7,20 | 899,69 | 168 | 0,60 | 0,08 | 0,66 |

| https://www.nimes.fr/ | Nimes | 29 | 4,17 | 2,32 | 5,13 | 715,84 | 167 | 0,52 | 0,07 | 0,55 |

| https://www.annecy.fr/ | Annecy | 27 | 9,60 | 6,74 | 2,98 | 619,48 | 123 | 0,64 | 0,10 | 1,12 |

| https://www.limoges.fr/fr | Limoges | 26 | 15,12 | 7,25 | 1,96 | 614,32 | 60 | 0,75 | 0,14 | 1,69 |

| https://www.tours.fr/ | Tours | 16 | 10,22 | 4,78 | 21,99 | 961,47 | 203 | 1,18 | 0,15 | 1,25 |

| https://www.strasbourg.eu/ | Strasbourg | 8 | 7,45 | 7,95 | 5,83 | 663,39 | 0,43 | 0,07 | 0,82 |

We have calculated the average of these data. On the general level we notice that the average ecoscore is 49, the energy consumed is 5,57 mAh, the percentage of CPU used is 2,22, the data exchanged is 6,36 MB, the RAM used is 689 MB, the number of requests is 99. Concerning the environmental impact we can observe that the carbon impact is 0,50 gEqCO2, the water footprint is 0,069 Liters and the soil footprint is 0,668 m2.

By dissociating the measurements from the remeasurements here are the averages that we obtain:

| Ecoscore | Energie | CPU | Données | Mémoires | Requêtes | Impact Carbon (gEqCO2) | Empreinte Eau (Litres) | Empreinte sol (m2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moyennes des remesures | 58 | 5.53 | 1.28 | 5.92 | 719 | 88 | 0.47 | 0.066 | 0.656 |

| Moyennes des mesures initiales | 41 | 5.61 | 3.16 | 6.81 | 658 | 111 | 0.53 | 0.072 | 0.680 |

The initial measurements were conducted on a Samsung Galaxy S7 smartphone running Android 8.

The remeasurements were performed on a Samsung Galaxy S9 smartphone running Android 10. The measurements were performed through our Greenspector Benchmark Runner tool, which allows automated tests.

Detail of the scenarios :

- Loading the application

- Reading the website in foreground

- Reading the page with scroll

- Inactivity of the website in background

Each measurement is the average of 3 homogeneous measurements (with a low standard deviation). The consumptions measured on the smartphone connected to a wifi network can be different when the smartphone is connected to a wired network. For each iteration, the cache is cleared beforehand.

Discover how Greenspector evaluates the environmental impact of digital services.

Valentine CANDELA is in charge of communication at Greenspector since October 2022. Graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in Marketing and Communication, she specializes with us in communication

Nantes Digital Week 2022: Ranking of the digital sobriety of partners’ and visitors’ websites

Last month we were present at the Nantes Digital Week. We participated in several conferences and workshops on the theme of responsible digital. It was an opportunity to meet many digital actors but also many visitors curious to know more about this vast subject.

On Thursday 22 October we ran the workshop “Hosting, measuring and designing virtuous websites” together with DRI and Webofacto. In this context, we measured the websites of several visitors and partners of the event.

The ranking in detail

The average carbon impact of one minute of navigation for these 98 partners is 0.45 gEqCO2, which is the equivalent of driving 2 metres in a petrol-driven car. Only 8 sites are above this average, which shows a good trend. The most sober website in this ranking (the CIC site, 0.19 gEqCO2) has 7.8 times less impact than the least sober site (Saint-Nazaire Tourisme, 1.5 gEqCO2).

The average power consumption (mAh) is 3.7 mAh and on average 9.01 MB of data is exchanged. In terms of web requests, the average is 73.

| Rank | Name | ecoscore | Carbon Impact (gEqCO2) | requests | Energy (mAh) | Data (Mo) | Memory (Mo) | Water footprint (Litres) | Surface footprint (m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CIC | 81 | 0,19 | 31 | 2,97 | 1 | 531,87 | 0,03 | 0,34 |

| 2 | Le Blog du Modérateur | 84 | 0,2 | 18 | 3,57 | 1,06 | 605,54 | 0,03 | 0,40 |

| 3 | La Cantine | 80 | 0,22 | 38 | 3,2 | 1,34 | 570,44 | 0,03 | 0,37 |

| 4 | Banque des territoires | 73 | 0,22 | 51 | 2,92 | 1,31 | 669,14 | 0,03 | 0,35 |

| 5 | Whome | 76 | 0,26 | 43 | 3,14 | 3,32 | 661,64 | 0,04 | 0,37 |

| 6 | sfr | 63 | 0,27 | 68 | 3,51 | 1,45 | 674,38 | 0,04 | 0,42 |

| 7 | Chateau des Ducs de Bretagne | 62 | 0,27 | 48 | 3,9 | 1,91 | 757,64 | 0,04 | 0,45 |

| 8 | BNP Paribas | 72 | 0,28 | 77 | 3,12 | 2,11 | 669,86 | 0,04 | 0,39 |

| 9 | Cobage | 67 | 0,31 | 72 | 3,3 | 3,15 | 582,25 | 0,04 | 0,40 |

| 10 | Mismo | 61 | 0,31 | 73 | 3,78 | 2,48 | 864,87 | 0,05 | 0,46 |

| 11 | Enedis | 52 | 0,35 | 57 | 3,5 | 5,91 | 716,59 | 0,05 | 0,42 |

| 12 | Sogetrel | 52 | 0,37 | 103 | 3,47 | 3,76 | 860,64 | 0,05 | 0,44 |

| 13 | Ecosystem | 36 | 0,37 | 52 | 4,93 | 4,33 | 744,72 | 0,05 | 0,57 |

| 14 | _icilundi | 69 | 0,38 | 27 | 3,37 | 9,48 | 661,03 | 0,05 | 0,40 |

| 15 | PALO IT | 61 | 0,39 | 87 | 3,8 | 5,04 | 708,84 | 0,05 | 0,47 |

| 16 | Université de Nantes | 71 | 0,4 | 61 | 3,46 | 8,16 | 650,39 | 0,05 | 0,42 |

| 17 | VIF | 51 | 0,41 | 112 | 3,79 | 4,41 | 826,63 | 0,05 | 0,48 |

| 18 | La Box Loire Atlantique | 63 | 0,47 | 91 | 3,74 | 8,63 | 650,42 | 0,06 | 0,47 |

| 19 | Radio Prun' | 50 | 0,48 | 44 | 3,56 | 12,92 | 712,56 | 0,05 | 0,43 |

| 20 | Maison Europe | 58 | 0,55 | 149 | 4 | 8,09 | 695,45 | 0,07 | 0,53 |

| 21 | Isefac Bachelor | 41 | 0,6 | 181 | 3,82 | 8,4 | 915,64 | 0,07 | 0,53 |

| 22 | Accenture | 35 | 0,61 | 63 | 6,92 | 11,29 | 647,93 | 0,08 | 0,80 |

| 23 | Tele Nantes | 48 | 0,8 | 146 | 3,43 | 21,39 | 821,12 | 0,08 | 0,48 |

| 24 | Groupe Onepoint | 57 | 1,11 | 84 | 3,36 | 40,15 | 744,13 | 0,10 | 0,47 |

| 25 | Saint Nazaire Tourisme | 47 | 1,5 | 70 | 4,16 | 58,42 | 761,91 | 0,13 | 0,57 |

Digital sobriety at Greenspector

As we talk more and more about digital sobriety, it’s important to come-back to this notion. Especially it’s a part of greenspector activity.

Definition

Digital sobriety is a global approach of digital, respectful of the earth and people.

Since few years, this topic takes more and more extent. We see this notion almost everywhere but often limited in consideration of environmental impact. For many Eco-design has been the gateway into the digital sobriety.

- Eco-design and digital environment impact consideration

- Digital accessibility and inclusion

- Attention economy

- Respect for personal data and privacy protection

- Cybersecurity

- Ethics

- Low tech and fight against technological solutionism

Various aspects of digital sobriety

Environmental impact consideration plays a crucial role in digital services. Beyond resources consumption related to their use (for example, energy needful to charge the battery), these services affect the user’s equipment: battery and components wear, memory and system surcharge… Those impacts motivate early change of latest and newer equipment.

However, today, the manufacturing of those equipments represents the phase of digital services with the greatest impact on the environment. It suits to create websites, mobile applications, and other digital services with as low impact as possible.

That’s why the repositories have been increasing. Examples include the GR491 of INR, the RGESN of DINUM, the 115 best practices or OPQUAST.

Add to this the law REEN as well as tools for evaluating the impact of digital services

Finally, we observe that the subject is gaining momentum and structuration. We can only delight even though there is a long way to go.

The benefits for users and companies are considerable. Overall, this approach improves the user experience (and in particular performance) as well as reduces development, maintenance and hosting costs. Similarly, the adoption of eco-design leads to the development of expertise, an improvement in brand image and constitutes a factor of attractiveness for customers but also for future employees

As a result, an eco-designed digital service will often have a smaller scope, which will facilitate its security, its compliance for accessibility and will tend to restrict the personal data collected.

Eco-design also tends to ignore mechanisms aimed at capturing attention (infinite scroll, autoplay of videos, excessive notifications, etc.). This also constitutes an ethical advance: the user is no longer just a consumer who must be retained by all possible means. We gain their trust and support by first providing them with quality service, tailored to their expectations.

Finally, by placing the user at the center of considerations, digital sobriety tends to avoid technological solutionism. This will avoid (among other things) going to digital services when it does not seem necessary. Sometimes a good old SMS can replace a website or a mobile application: a low-tech solution can meet user needs just as well (sometimes even better).